Beethoven’s “Für Elise” and the Ritual of Garbage Collection in Taipei (垃圾車來了!)

- Shashwat

- Nov 2, 2025

- 6 min read

People in India are very easily ashamed, disgraced, annoyed, angered and outraged by dirty streets, overflowing garbage, mountains of landfills that grow mound by mound over a pond, a lake, a river, and turn what could have been sites of repose and proximity to the natural world into hellscapes that remind us of our banishment from paradise here on earth.

Imagine my surprise, then, on finding no trash cans on the streets of Taipei. Intuition leads us to believe that the absence of garbage bins means proliferation of trash, but the streets are clean, it is difficult to find litter, and one may not hesitate a moment to sit on the roadside, and rest on the pavement, gazing at the passing blur of cars, scooters, bicycles and pedestrians.

7-Elevens and MRT stations are some exceptions. Whatever trash I collect as remains of the day’s consumption, of sandwiches, cups of coffee or tea, I carry with me, in the small section of my backpack or shoved into the bottle section as wrappers, plastic wraps waiting for the usual trash can at the MRT or some convenience store.

Every city has its share of homeless, the poor folks, wearing rags and walking about aimlessly, falling asleep on a bus stop bench or some park in the shade of trees, or lying gathering dirt and grime, ignored and erased from mind and memory as sores in the eye of the slightly luckier, for now at least.

Notions of heightened individualism – nurtured by an upbringing and an education that rewards high grades, degrees and diplomas, designations and awards that are seen as so many marks of merit before a name we take as our own so closely – make us forget that whoever we are, whatever we are, wherever we are, are the results of fortunes and misfortunes, strivings and struggles of a wider world of which we are but small parts of a whole that sustains us by their sweat and labour.

Relentless pursuit of individual accomplishments engenders a somewhat ridiculous notion that we stand entirely on our own feet and turns us blind to the shoulders that uphold us in our daily needs, that it is almost impossible to go another day, another hour, without the unseen many who nourish us with their sweat and blood without receiving a fair share of the sky, the air, a roof, and dignity that we so ardently assume as our rightful privilege.

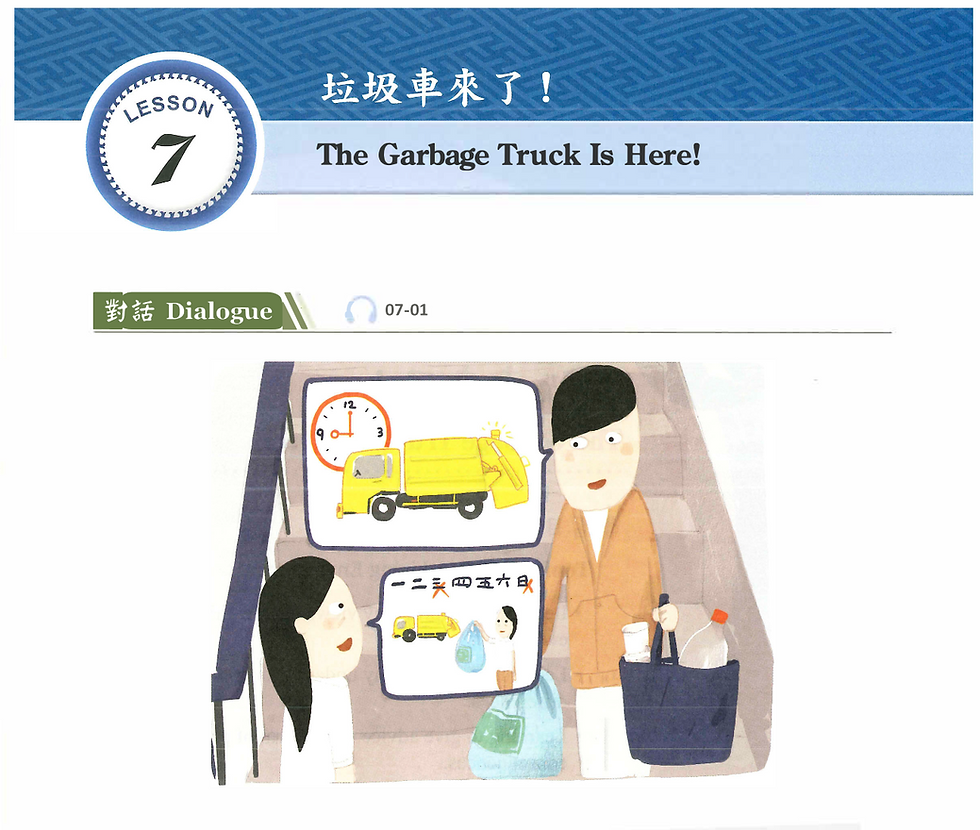

Every evening, Beethoven’s Für Elise echoes through the streets of Taipei City as harbinger of the Le Se Che(the Garbage Collection Trucks) that come on a fixed schedule to fixed spots. Hearing the music, my friends and I rush to prepare bags of cans, bottles, plastics and cardboard, papers and electronic disposables, biodegradable refuse, and compost of the days and weeks’ leftovers, nicely segregated to be taken to the trucks on pre-decided days of the week, Monday for Paper recyclables, Tuesday for Electronics, and so on.

The entire neighborhood comes together, lugging the waste generated, produced and proliferating to sustain their existence, walking towards the trucks, and waiting patiently in queues. The first time I notice the Le Se Che, I am sauntering through the quiet streets and alleys by Xiaobitan. I had decided to let go of the public transit for the day and walk back home from Da’an towards Xindian and up the hill where the G-9 bus usually brought me to my haven in the International House of Taipei.

I notice the faint echoes of the music. It was at once so familiar and yet so new, I should say up front my familiarity with Classical music amounts to less than an amateur’s and whatever I have heard has come as background score in some film or courtesy of YouTube autoplay, some evening spent in company of friends with finer taste in music and indulgence of my ignorance of matters musical and sublime.

Following in the footsteps of the music, I see the quiet and empty alleys begin to hum with movement. Doors opened and people began to bring out garbage bags and stack them against the building’s walls. Others begin to haul the garbage on their backs and merge with crowds gathering near some spot, exchanging a few words, and waiting. The music grows louder, and a note of engines is added to the symphony.

Dressed in neat uniforms, wearing gloves, the city's essential workers pull back into the collection spot. The automatic doors roll back open, a worker climbs on top, the queues begin to move slowly towards him, hand him the recycle bag, the man empties it inside the truck and returns the reusable garbage bag, the next in line moves forwards, the ritual repeats itself.

Another truck collects the non-recyclable, and a smaller one places a canister into which people empty their compost, catching their breath to reduce the foul exposure to a minimum. So many times, I stand in similar queues with my friends and flatmates. Lazy, we always wait until the waste begins to overflow and sprawls all over the kitchen. When it appears that we cannot let the garbage accumulate for another day, a movement begins, and out we emerge into the streets, carrying three-to-four big bags a person towards the Le Se Che and the music of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony, which echoes as its harbinger.

The garbage truck scenes I witness unfolding over the months soon appear in the Chinese class, during the second three-month term, when an entire chapter is solely devoted to the Le Se Che, garbage segregation and disposal. I learn the words and Chinese characters for my experience on the streets.

Compared to the dignified look in the eyes of their counterparts in Taipei – their automatic trucks, uniforms and safety gloves – my Indian brethren bear a heavy burden as acutely mental and psychological as physical. They, too, have their own music, ‘gadi wala aaya bhai kachra nikaal,’ (the trolley comes, come out with your trash). Instead of trucks with automated doors, they come in manual trolleys, lucky if they come retrofitted with some imperial smoke-spitting engine. They wear no gloves, and must go door to door. There is no segregation. Medical waste and needles come mixed with vegetable peels, newspapers and plastic with broken glass and rusted metal.

A friend who observes these operations up close tells me women spend their days sifting through the garbage manually, spending their day in smells we are so ready to flush and wash our hands from, while they separate our tatters from shit, blood from bones.

At every red light,

my heart sinks,

and murmurs a silent prayer,

oh, mother land of mine,

why so cruel to your progeny?

Through the open windows

and knee-high doors

of an auto-rickshaw,

Stephen Spender’s children peer

through eyes sunken deep into darkness

and bony cheeks,

perform some acrobatics

or sell a pencil or a pen,

and an emaciated rib cage pokes through fleshless skin.

Two millennia and a half ago,

the Boddhisattva of our age

renounced the path of physical hardship –

A grain of rice and a drop of water

do not lead to nirvana –

Why do we, then, torture our children so?

For what enlightenment,

We inflict such a fate,

worse than "An Elementary School Classroom in a Slum"?

As red lights turn green,

how they vanish from our sight and sense

picking our garbage, sniffing some glue,

while we sip from our cans without a fucking clue!

Why does their hungry sight

not arouse a rebellion,

disaffection with this cruel, heartless world

when a pile of trash,

a stinking river,

and dirty streets,

so readily arouse indignation.

Beethoven’s jingle shifts from Doppler's blue to red as approaching trucks begin to depart for the night. Ritual tryst with the Le Se Che over, people walk home, carrying garbage bags, now emptied of all trash from the day and week. The jingle echoes long in my mind. It returns often unsuspecting, like an earworm, bringing memories, evoking dreams: one day perhaps, some piece of classical music will echo through our streets, edify the lives of our brothers, accord them the dignity they deserve, a pair of safety gloves, and bring us together in a ritual of equality and justice for all. It does not seem like that big of an ask!

Comments